Dorothée-Myriam Kellou is a journalist, filmmaker, writer, and podcaster whose work explores memory, postcolonial legacies, migration, and the intimate intersections of personal and collective histories. She investigates the effects of forced displacement, colonial and postcolonial violence, and the silences surrounding these histories, with a particular focus on Algeria, France, and the broader MENA region.

Literary Work

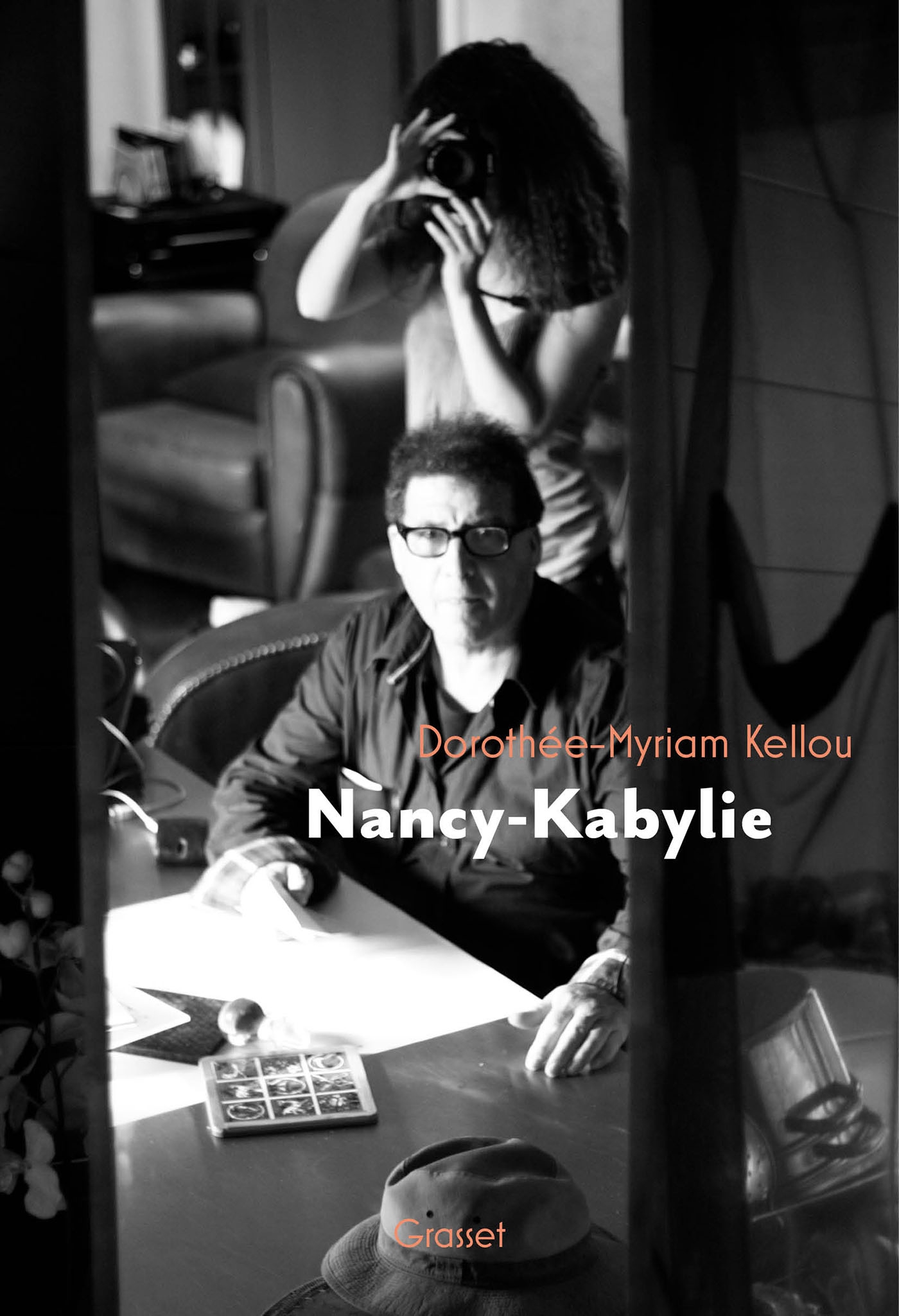

Her first book, Nancy Kabylie (Éditions Grasset, 2023), examines the lasting effects of French colonial resettlement operations in Algeria. The book combines memoir, essay, and historical investigation to trace her own family history while exploring broader questions of uprootedness, identity, and reconciliation between France and Algeria. Nancy Kabylie received the Prix littéraire de la Grande Mosquée de Paris for its innovative engagement with memory, history, and postcolonial narratives.

Filmmaking

Kellou’s first feature film, In Mansourah, You Separated Us, interweaves ethnographic research with personal and collective memory to explore the experiences of Algerian communities displaced during the French colonial war. The film was coproduced in France, Algeria, and Denmark, screened at major festivals including IDFA (Amsterdam) and Visions du Réel (Switzerland), and received the Human Rights Award at Fidadoc (Agadir, 2020) as well as the Étoile de la Scam (France, 2021). It is distributed in the United States by Icarus Films.

She is also the founder and president of Rawiyat, a collective of women filmmakers from the Middle East, North Africa, and the diaspora. Established in 2020, Rawiyat provides mentorship, professional support, and networking opportunities for women filmmakers, aiming to sustain their creative careers while fostering a collaborative and critically engaged community.

Journalism and Podcasts

Kellou has reported across the MENA region in French, English, and Arabic for outlets including France 24, Arte, Le Monde, France Culture, and Orient XXI. Her investigations include the 2016 exposure of Lafarge’s indirect funding of the Islamic State in Syria, which earned the TRACE International Prize for Investigative Reporting, and has had legal and international repercussions.

In addition, she produces podcasts that explore postcolonial memory, Algerian uprootedness, and the intersections of history, identity, and contemporary social issues. These projects blend investigative journalism with intimate storytelling, offering nuanced insights into historical and cultural legacies.

Counter-Monument Work

Kellou has contributed to public memory and postcolonial discourse through collaborative artistic projects, including the counter-monument to the colonial statue of Sergeant Blandan in Nancy, France. The Disorientation Table—a circular metal installation engraved with poetic texts in French, Arabic, and Tamazight—invites reflection on France’s colonial past and its continuing presence in public spaces. This project blends historical research, artistic practice, and public engagement, highlighting the intersections of memory, history, and contemporary civic dialogue.

Awards and Recognition

Kellou’s interdisciplinary approach blends literary writing, filmmaking, journalism, and podcasting, often focusing on the interplay between historical memory and contemporary social, political, and cultural issues. She has recently been awarded the Recanati-Kaplan Prize, recognizing her outstanding contributions across her career in research, writing, and creative media, and highlighting her role as an important voice in postcolonial studies, Arab diaspora studies, and contemporary cultural production.

Public Engagement

Kellou’s work has been presented in over 100 conferences, festivals, and academic institutions worldwide, including panels on postcolonial memory, diaspora filmmaking, and investigative journalism. She is available for lectures, workshops, and conferences, actively participating in public and academic dialogue that bridges scholarship, media, and creative practice.